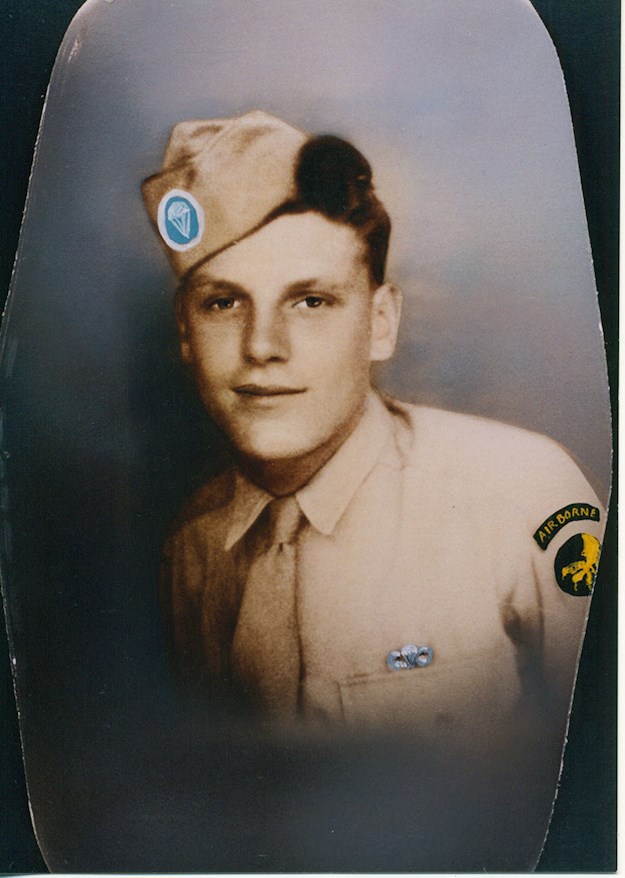

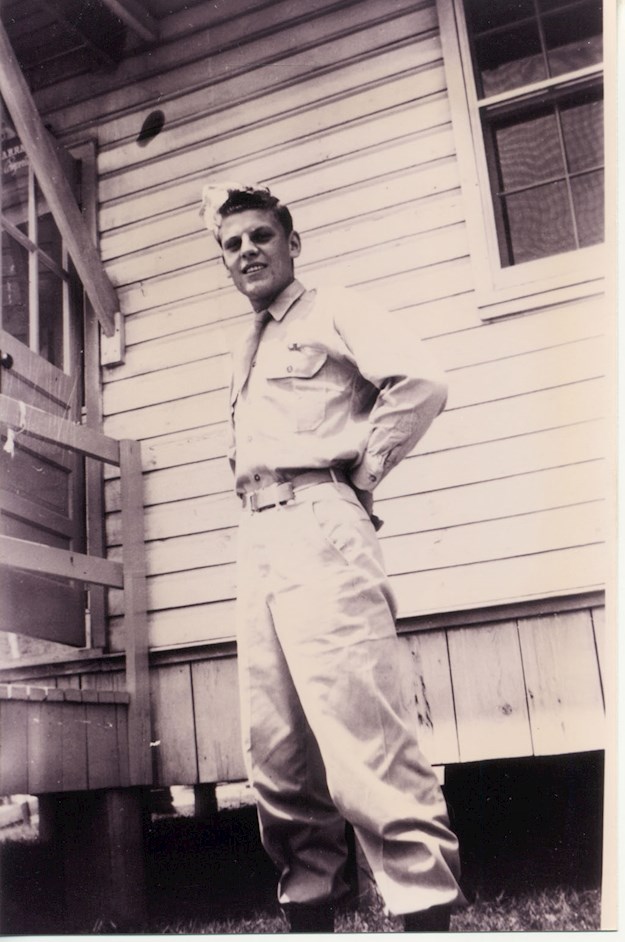

Fred Glavan left high school in Minnesota to join the elite American airborne forces. It took a long year of rigorous training before he received the proud paratrooper’s wings. Early in 1945 Fred’s unit was thrown into the Battle of the Bulge. In less than a week he was dead.

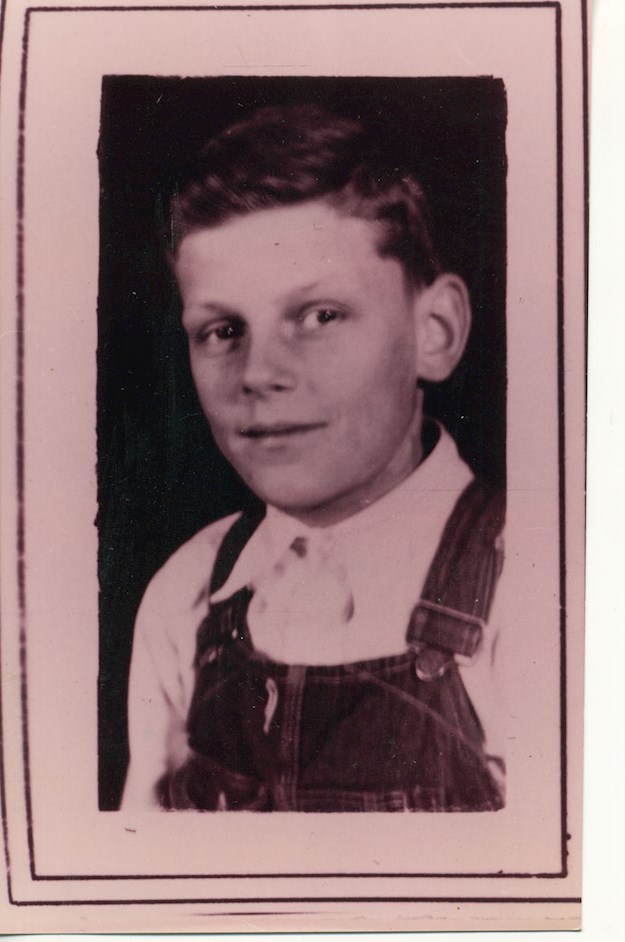

The seventh of eight children, Fred was the son of immigrants from Slovenia who had settled in Minnesota’s Iron Range, a mining area. During the Great Depression, in his adopted hometown of Kinney, Fred’s father scratched out a living as a miner and school janitor. Fred’s call to duty came when he turned eighteen. His parents were worried sick. Three of Fred’s older brothers were already fighting in Europe; two others had been sent to fight the Japanese. Fred’s brothers had remained safe thus far, and the siblings tried their best to write letters and stay in touch across the far-flung theaters of war.

Fred was proud to be part of the 17th Airborne Division and excited about the prospect of his first battle jump. But when the Battle of the Bulge erupted, his unit was hurried to the frontlines west of Bastogne not in aircraft but in trucks. The paratroopers stormed the enemy a first time at the start of 1945. The enemy quickly beat them back. Early on Sunday 7 January the Americans launched a second attack through deep snowdrifts, dense fog and bone-chilling wind. Fred did not get far. A bullet from a German sniper hit him in the chest, killing him almost instantly.

A sister-in-law sent the heartbreaking news to Fred’s five siblings in the distant theaters of the Second World War. “I never will be the same man,” replied one anguished brother, a tank commander in the Philippines. “Why did it have to be him?”