1944 was the year in which Horst Helmus turned eighteen. For several years, the German from Gummersbach, a town east of Cologne, had been spared the worst effects of the Nazi wars of aggression. But Hitler’s last gamble in the Ardennes changed all that in the blink of an eye.

Gummersbach was a sleepy town with a picturesque medieval church that appeared unlikely to attract the horrors of war. True, some townspeople had disappeared, apparently because of their Jewish blood, but this was only whispered about. And Horst Helmus was well aware that more than one thousand British bombers had ravaged Cologne as early as May 1942, but that was fifty kilometers away.

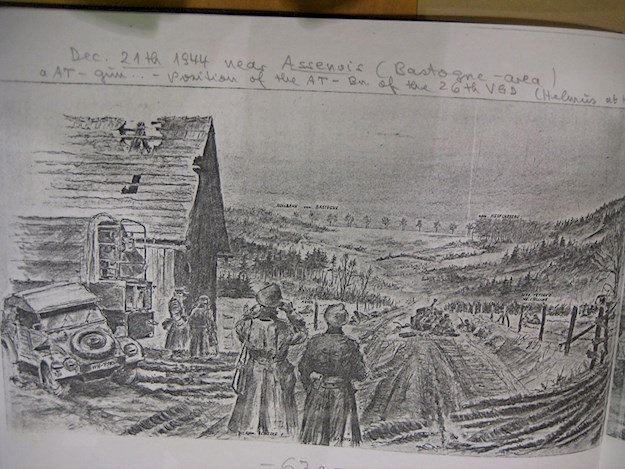

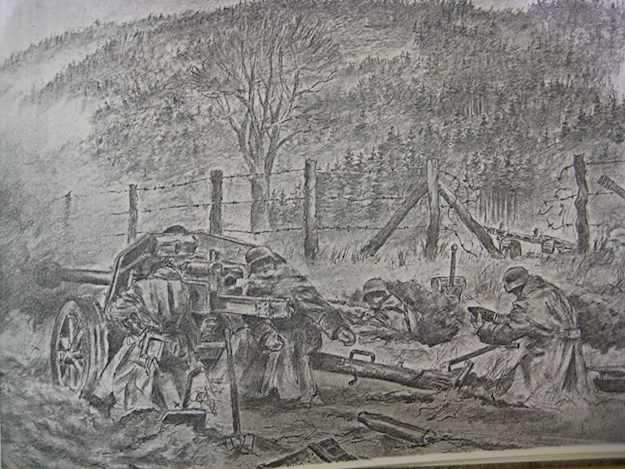

Gradually, the war sneaked closer. In December 1943 an air raid unexpectedly destroyed parts of Gummersbach. In December 1944, Horst suddenly found himself in uniform as part of an anti-tank battalion. The atmosphere among the men in his unit, the 26thVolksgrenadier Division, was electric. They were poised for fighting the Allies and taking revenge for the bombing of their homeland and the defeats in Normandy and Russia. “I am so excited that I feel wound up,” Horst scribbled in his diary. “The same goes for my comrades.”

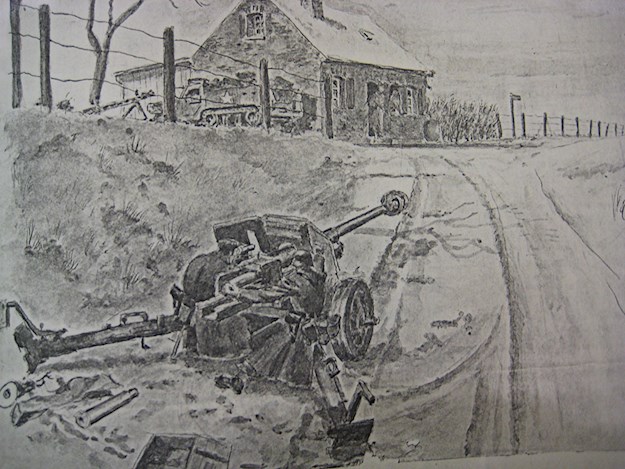

But as Horst and his comrades tried in vain to make their cannons defeat the Allied forces in the Ardennes, they discovered that there was no glory in war. Fighter-bombers pounced from the sky, “again and again,” Horst observed aghast, “driving us insane.” At the end of one strafing raid, Horst was devastated to find a fellow eighteen-year-old who had become his friend dead in a puddle of blood that had pulsed from a cut artery. Horst survived the war and returned home, trying hard to make sense of his experiences in a series of poignant drawings.